Government’s unsustainable fuel related levies and taxes.

**This opinion piece was first featured in the Daily Maverick**

There is a position that says more taxes aren’t necessarily a bad thing, as these get ploughed back into the infrastructure spending of a developmental State, which improves the economy. That’s true, if it happens that way. Sadly, ours is often wasted through gross inefficiencies in leaky procurement processes that pays three times the price for infrastructure that we don’t often need, while a whole lot is lost to corruption.

The end result is over-spending and less delivery which stimulates the angry Taxman to seek more revenue, often through a short-term mindset by increasing taxes or borrowing more money, both of which can lead the country into a cul-de-sac of reduced prosperity and even that of a failed state. Of course, this depends on how exactly the money is spent and the value for taxes paid is experienced by the citizens.

Too often, the tax increase envelope is pushed too far and the purpose of specific taxes gets lost or challenged, placing the State in a precarious position when income from existing or planned revenue streams begin to fail. Good examples include SABC’s TV Licenses and Sanral’s e-Toll scheme. Reduced consumption of taxable goods, combined with technological and environmental changes, has and will continue to reduce some State revenues, which is a quandary that looms large for the various levies and taxes attached to the sale of petrol and diesel.

The price of petrol in South Africa is subject to not only the price of fuel when it lands in the country, but also by eleven other components lumped into the cost per litre of petrol and diesel sold to the consumer. All of these components, taken together, have a significant impact on the price of this important commodity. Retailers, wholesalers, and logistics companies of all sorts absorb such growing costs by shifting it downstream – increasing the cost of living for all citizens.

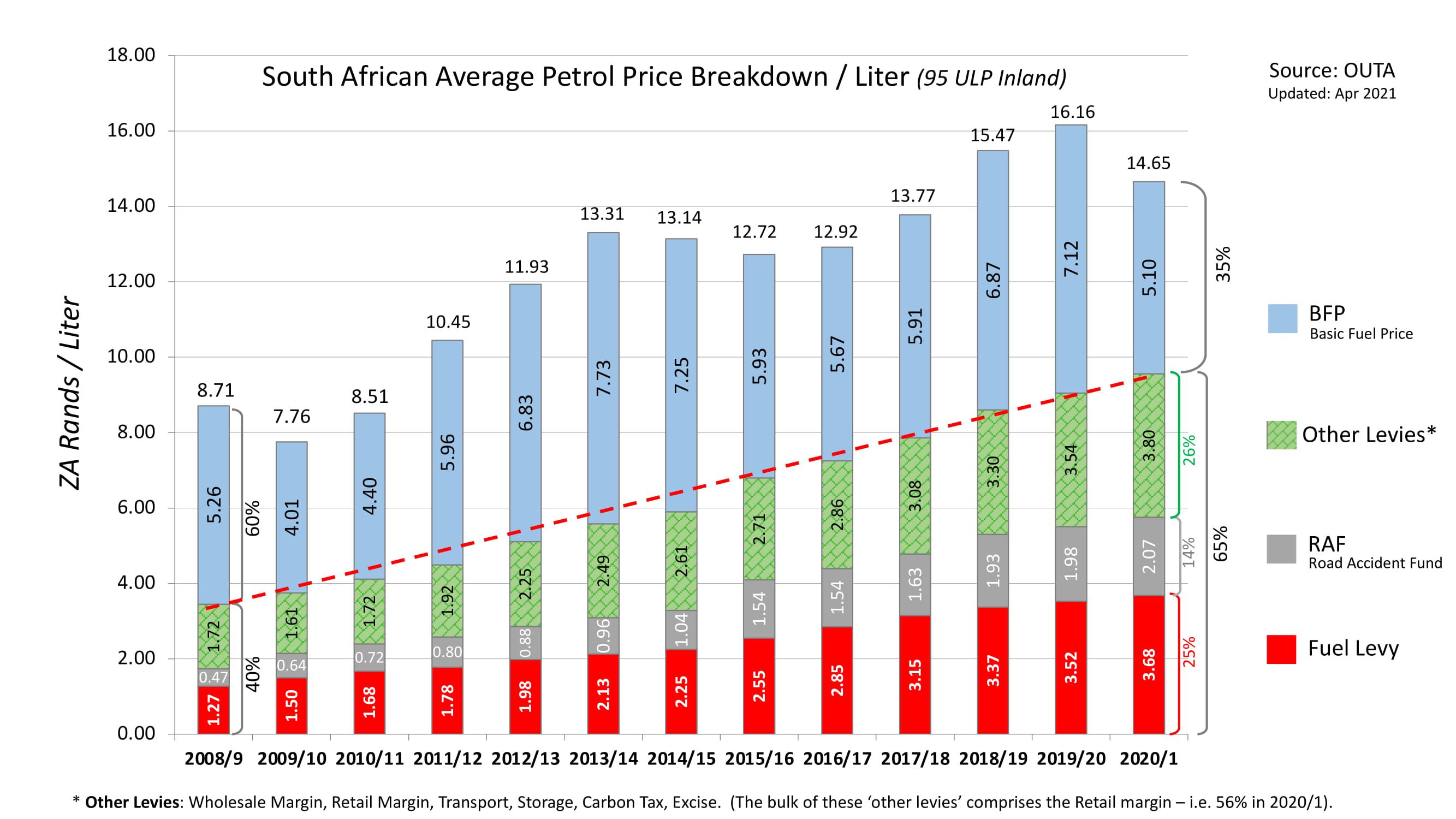

When one looks back at the trends of these various ‘additional levies’ and what lies ahead for the sale of petrol and diesel in a changing vehicle propulsion environment, these additional taxes and levies appear to be unsustainable. More worrying is the ratio of the Basic Fuel Price (BFP) versus these other levies and taxes in the total price of petrol. This ratio has become inverted over the past decade, suggesting that the State should heed the impact they are having on our competitiveness as a nation through the over-taxation of petrol.

To understand this a little better, the Basic Fuel Price (BFP) fluctuates rather significantly on a monthly basis, due to the two influencing factors of the Rand/US Dollar exchange rate and the international market price of Brent Crude oil. However, virtually all the other components making up the price of petrol and diesel are static on a monthly basis, barring an annual increase applied to the respective elements. Following years of constant increases, the total of these ‘additional levies’ comprise the bulk of the price of fuel, which was not the case too long ago.

The annual average component of the BFP over the past 13 years is R6.00 per litre of petrol (95 ULP inland pump price). It is a component that has ranged between R4.10 on average in the 2009/10 year to R7.73 in 2013/14 period. Obviously when one looks at the BFP range variations on a monthly basis, this has fluctuated between R2.74 in January 2009 and again in May 2020 at the low end, to as high as R8.62 / litre in March 2014 at the top end.

The graph below tells an interesting story about the growing impact of other charges, the first of which is evident in the year ending March 2009, whereby 40% (or R3.45) of the average price of petrol in that year (R8.71 per litre) was attributed to the sum of these additional levies and fees. The actual BFP of the commodity made up the other 60%. Twelve years later, that ratio has become inverted, with only 35% of the average price of R14,65 per litre in 2021 being attributable to the BFP (i.e. R5.10) and 65% to taxes and levies (R9.55).

The main levies attached to the sale of petrol and diesel are explained below.

Fuel Levy: This is a direct tax on motorists which is channelled straight to Treasury and is not ringfenced for roads as many believe. Initially justified as a user-pays levy to build road infrastructure, this income which now generates over R85bn per annum, more than compensating for road construction and maintenance and is regarded as a soft target tax on motorists who supposedly should be able to afford these taxes. The fuel levy at R1.27 in 2009 (15% of the price of petrol) now stands at R3.83 per litre since April 2021, accounts for around 22% of the petrol price.

The Road Accident Fund (RAF), which in 2009 made up 5% of the price of petrol and generated around R9bn per annum for vehicle related injury compensation, now makes up for 14% of the fuel price and pumps around R45 billion into the RAF. This specific ‘tax’ has undergone a number of substantive increases (from R0.45c per litre in 2009 to R2.18 in April 2021), in order to keep pace with the growing demand on these lucrative revenues which are largely wasted due to inefficient administration, corruption and unscrupulous legal claims which the RAF administrators are too weak to challenge.

The Other Levies and fees go toward retail and wholesale margins, carbon tax, excise duties, transport and storage costs. These combined charges have increased from R1,72c per litre (20%) of the fuel price in 2009 to R3.80 (or 26%) by 2021. The Retail Margin (which goes to the petrol station management due to the regulated petrol price structure), has accounted for just over half of the ‘other levies’ component of the fuel price.

Opinion piece by OUTA's CEO Wayne Duvenage.